Each October, the world pauses to hear who will receive the Nobel Peace Prize, an award that has, for more than a century, symbolised humanity’s highest aspirations. Once a moral compass in a fractured world, it has celebrated figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Nelson Mandela and Malala Yousafzai, people who risked everything to make peace not just possible, but visible.

But in 2025, amid global crises that stretch from Gaza to Kyiv to the climate emergency, it’s fair to ask: what does the Nobel Peace Prize mean today? Is it still a force for moral clarity, or has it become a comfortable ritual for an uncomfortable world?

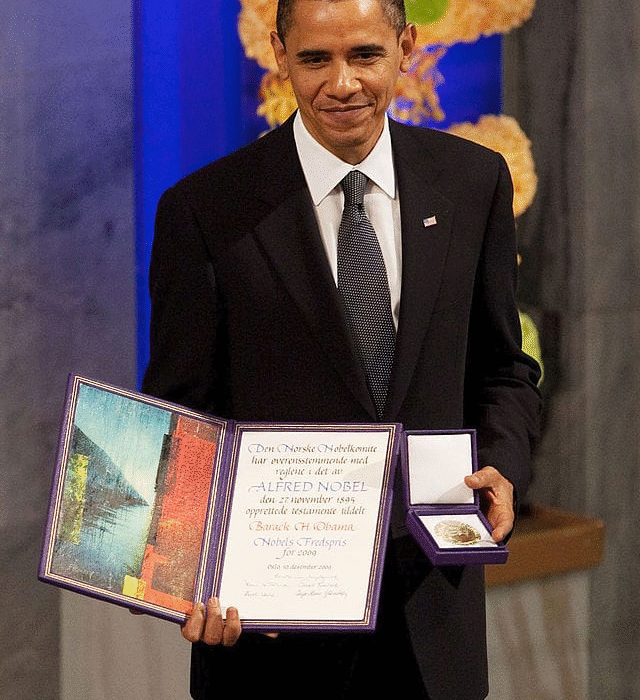

In recent years, the Nobel Committee has faced growing criticism for inconsistency and political caution. The award to Barack Obama in 2009 – granted barely nine months into his presidency – felt more like a hope than a judgment. The 2012 prize to the European Union was seen by many as a diplomatic nod rather than a recognition of genuine peacebuilding. Critics argue that the committee’s choices have at times mirrored Western political priorities rather than challenged them.

Yet to dismiss the Nobel Peace Prize as obsolete would be too easy. The world’s idea of peace has evolved, and so has the prize – if unevenly. Where once it honoured statesmen who ended wars, it now increasingly celebrates those who prevent them through truth, justice and environmental stewardship. The 2021 award to journalists Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov for defending free expression, or the recognition of climate campaigners and human rights defenders, shows a broader, more modern understanding: that peace cannot exist without democracy, sustainability or human rights.

In a time of populist politics and disinformation, the Nobel Peace Prize still offers something rare: a global platform that can elevate the brave over the powerful. Its symbolism endures not because it is flawless, but because it insists, however imperfectly, that moral courage matters.

Still, if it is to remain relevant, the Nobel Committee must hold itself to the same standard it expects of others. Greater transparency, a wider global perspective beyond Europe and North America, and the courage to challenge major powers, not just honour safe choices, would renew the prize’s moral authority.

Ultimately, the Nobel Peace Prize matters not as a verdict but as a question. Each year, it forces us to ask: what does peace look like now? Who is working for it, often unseen and unthanked? And are we, as a global community, prepared to follow where that question leads?

For all its contradictions, the Nobel Peace Prize still offers something the world desperately needs, a reminder that peace is not an abstraction but an action. As long as people continue to fight for justice, truth and human dignity, the prize will still matter, not because it defines peace, but because it dares to keep the conversation alive.